4/5 Stars

‘No Room for Man’ , with its minimalist, abstract cover illustration and slightly larger-than-mass market-paperback size, was conceived and published for use as a textbook. Editor Martin H. Greenberg (University of Wisconsin) is of course the ‘Martin Greenberg of 1000 anthologies’ fame, while co-editors Ralph Clem and Joseph Olander of Florida International University also were / are active in producing SF anthologies for both popular literature and classroom purposes.

‘Room’ is a rather curious anthology; it was published in 1979, by which time the ‘Population Bomb’ phenomenon pretty much had run its course and was in fact rapidly dwindling. It could be argued that ‘Room’ appeared at least five years too late. By ’79 the impact of Paul Ehrlich’s work, and that of fellow Bombers like William Vogt, Garrett Hardin, William and Paul Paddock, and Hugh Moore, had receded from the public consciousness, although it still resonated in the consciousness of what is now called the ‘international development’ community.

Without bogging down in an extended treatise on political or social controversies, how does ‘Room’ stand on its own as an SF anthology about overpopulation ? Quite well, in fact. [All of the stories in the anthology previously appeared in print between 1955 and 1976].

The book opens with J. G. Ballard’s ‘Billenium’, still a very effective tale despite appearing way back in 1962. It’s a deftly written look at the sociology and psychology of overcrowding; in a real sense it is the precursor to Ballard’s later novel ‘High Rise’.

Brian Aldiss contributes ‘Total Environment’, in which 500 young Indian couples are shut away in a sizeable structure and left to their own devices for more than a quarter-century as part of a (rather unethical) experiment to see how humans adapt to severe crowding. As the first 25 years approach expiration, a scientist is sent inside the structure to investigate what appear to be ESP powers among the teeming, fecund inhabitants. Nowadays the story would be considered VERY politically incorrect and would enrage Indians (marasmic Hindus in particular) as much as the spectacle of Richard Gere kissing Shilpa Shetty . The narrative suffers from abrupt jumps from one set of characters to another, all in the absence of adequate exposition about the why and wherefore of the Environment experiment. Despite these flaws, it still has a kind of voyeuristic appeal…something that the tourists of ‘Slumdog’ Bombay (Mumbai) must feel !

Two of the stories in the collection served as the basis for later novels. Harry Harrison’s ‘Roommates’ was expanded into ‘Make Room ! Make Room !’ which in turn became the basis for the feature film ‘Soylent Green’. ‘Roommates’ is a great overpopulation story, that’s all there is to say. Robert Silverberg’s ‘In the Beginning’ was later expanded to the novel ‘The World Inside’. ‘Beginning’ deals with a far-future society in which 75 billion people live their entire lives distributed among the floors of 3 km – tall skyscrapers, or ‘urbmons’. The story focuses on the psychological trauma experienced by a young woman who faces moving from one urbmon to another. In my opinion the story was a bit too subdued; the almost-magical advanced tech of the urbmon world has the effect of depleting the narrative of any real tension.

Cyril M. Kornbluth contributes ‘Shark Ship’, in which the near-future earth deals with overpopulation by creating vast fleets of crowded ships that endlessly sail the seas harvesting plankton to feed and clothe the multitudes on board. For at least the first half of the tale it’s a well-envisioned setting, and the thin margin for life or death aboard ship is effectively communicated. Unfortunately, the story’s second half takes a rather bizarre and obtuse turn into late 50’s ‘beat’ phrasing and social satire. One of the weaker entries in the anthology.

Mr. Population Bomb himself, Paul Ehrlich, contributes ‘Eco-Catastrophe !’ in which he lays out a fictionalized course of events that sees the world going through mass starvation and ecological collapse in the 1970’s and Edward ‘Teddy’ Kennedy as President ! Whether or not one is a devotee of the Bomber philosophy, it’s an effective essay, and some might argue it retains its relevance today, forty years after first appearing in print.

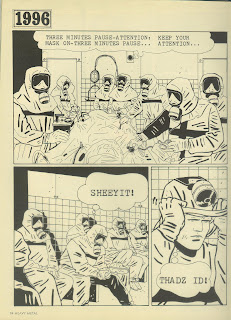

Frank M. Robinson cleverly depicts an ultra-polluted LA megalopolis in the early 21st century in ‘East Wind, West Wind’. Things are so bad that smoking a cigarette is a misdemeanor and owning a carton a felony ! People lurch around the streets in the dim light of mid-afternoon choking and pulling on gas masks. Someone out in the Hollywood Hills is in possession of an illegal internal combustion engine vehicle and the narrator is on the case. ‘East Wind, West Wind’ effectively communicates pollution paranoia ca. 1970 and it’s one of the better stories in the collection.

Frederik Pohl’s ‘The Census Takers' deals with a near-future world in which overpopulation is solved via radical means. The main storyline contains enough inherent drama, yet Pohl subtracts from it by including a rather contrived Sci-Fi subplot that leads to a not-so-surprising ending.

Maggie Nadler’s ‘The Secret’ is among the best entries in the anthology. In a near-future, overcrowded world where parents are permitted no more than two children, can someone get away with breaking the rules ? ‘The Secret’ takes place entirely within the apartments and hallways of a dingy tenement, and involves a small cast of characters, but nonetheless delivers a harrowing example of how people under stress can commit the most quietly vicious of acts.

‘Statistician’s Day’ by James Blish deals with England in 1990, after the world-wide Famine of 1980 led to the implementation of mandatory birth control. It’s one of the few SF stories I’ve ever read that references the Chi-Square test - ! As is typical with Blish, the tale has an understated tone, and seems a bit lacking in energy compared to some of the other entries in the anthology.

How can an illiterate Third Worlder, whose single recreation in an otherwise drab existence is sex, be persuaded to remain chaste during his wife’s fertile period ?

This line of dialogue from ‘Triage’, by William Walling, unapologetically signals a story that bases its narrative on the Population Bomb ethos. Set in the near future, when Ehrlich’s Eco-Catastrophe has indeed come to pass, Dr Victoria Duino helms the UN Department of Environment and Population (UNDEP), where she is forced to make routine decisions as to whether or not to deliver food aid to starving millions in Egypt and other squalid hellholes. Duino is a sympathetic character despite having to play God on a continuous basis; her battles with factions on the conservative and liberal sides of responding to the Eco-Catastrophe define the story's narrative.

‘No Room for Man’ closes with two very brief (i.e., two-page) short-shorts. Theodore Cogswell’s ‘Probability Zero !’ is a humorous look at the statistical fallacy of back-calculating from one’s family tree in order to arrive at an estimation of the number of people alive in preceding generations. ‘Doll’s Demise’, by George Guthridge, examines the psychology of child-bearing in the context of population control efforts, and in its oblique way reminds the reader that appeals to common sense and logic may be fallible in the absence of an understanding of the whys and wherefores of reproduction.

All in all, ‘No Room for Man’ is a very readable and informative anthology, and it’s too bad it was never released in a mass-market paperback format. It’s an interesting take on the latter years of the Population Bomb era, and readers of SF at that time may find some nostalgia within its pages. And anyone curious about how writers dealt with one of the first ‘Eco-Catastrophe’ themes of modern pop culture will find worthy material here.